Joe: In my memoir, Kitchen Arabic, I stated that “To be a man, you first need to see a man.” In some ways my father had been a positive exemplar, but in many ways he had not been. Growing up I found myself seeking role models in teachers, clergy, the dads of my friends. I was in my forties when I met Fern’s father and I realized that here was just the kind of man I had been seeking all those years ago. To my regret, I knew Milt Yasser for too brief a time.

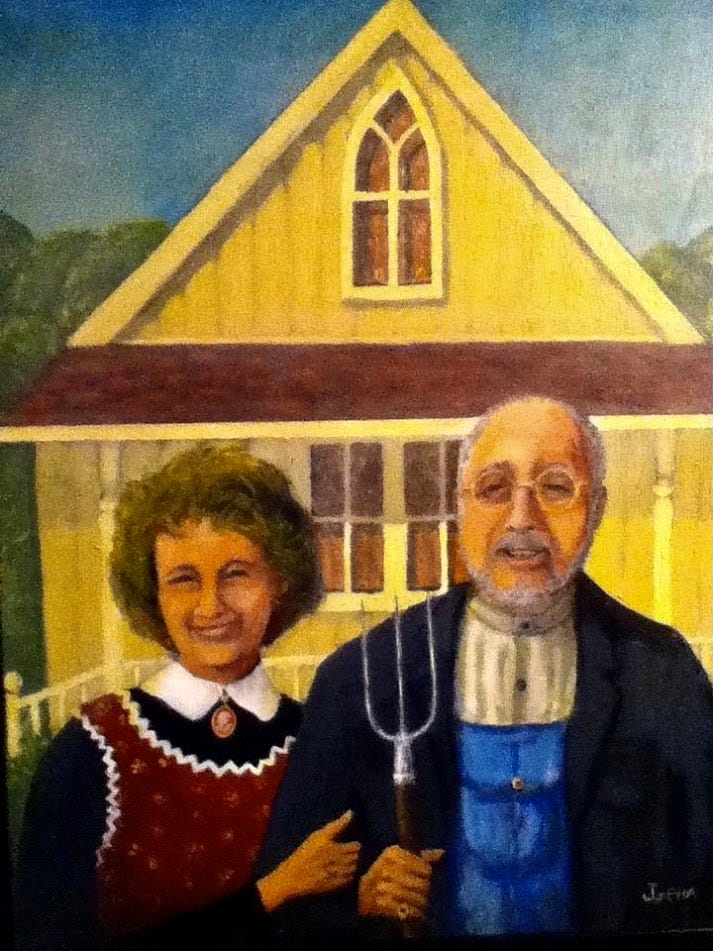

Today, our Fathers’ Day piece is about him, and to present him properly, I’m handing the column over to Fern.

Fern: Once I told a friend that my father often woke me for school by standing in the doorway of my bedroom, calling my name and when I looked up from the pillow, he would say: “Oy, you are such a mieskeit. I can hardly stand to look at you.”

When I revealed what mieskeit meant – it is Yiddish for ugly face – my friend was appalled.

I explained. “He didn’t really mean I had an ugly face.”

She asked, “But didn’t you feel bad? That’s mean. To call a child ugly.”

Telling the story even now, seeing through another person’s eyes, I could understand how my father’s teasing would be interpreted. But I always knew that what my father meant those mornings when I lifted my face from the pillow was: “You are beautiful and I love you so much that I can hardly bear to look at you.”

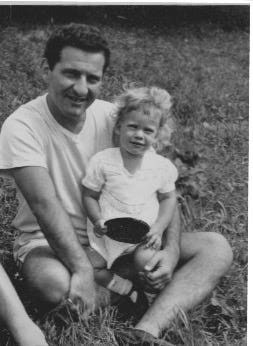

I am part of a generation who had mostly “good enough” fathers. A good enough father made a living and didn’t drink or hit. Good fathers came home from work and read the paper while mothers took over the emotional needs of the children. My dad was there in that, too. He knew the names of all my teachers and listened as I read aloud the stories I wrote in English class. He came home early from work and went to all my brother’s baseball games.

There was a certain confidence that dad had with his role. There was not a lot of negotiating. He said no with surety. There were catch phrases that pretty much summed up his moral stance: Some things were simply “not necessary.” Don’t “take more than you need.” Some behavior was not permitted because “it isn’t even nice.”

My dad was good. And my brother and I were part of him, so we were good, too. With my father I always felt loved. And safe. I never knew that not everyone had a father who could not be trusted. And I didn’t know until I was an adult that men could be unfaithful or selfish or violent.

My father was almost eighty when his inoperable lung cancer spread. I took off a semester of teaching to be with my parents in Florida and the weeks that followed were organized around eating, cleaning up, bodily functions and sleep. Hospice came and went. I witnessed my father’s decline from day-to-day, yet in slow motion all the same.

The hospital bed was set up on the enclosed porch of my parents’ condominium. Through the windows you could see the blue sky, the palm trees, the pink hibiscus. The oxygen tank, the wheelchair, the commode, lined one wall. I learned how to lift my father to sit up in bed and to administer morphine. I went to the grocery store and to the mailbox. Once I took his car and went out for a manicure. As the girl put a sandy blush on my nails, I thought: My father is dying.

During the last week of his life, my father’s concern for his family remained strong. “Did you give Mommy breakfast?” he would ask me first thing in the morning, though he was too weak to eat himself. And slipping in and out of consciousness, he would turn to me: “Fernie, you got enough money?”

My brother came down two days before Dad passed. We walked around the small apartment, listening to his ragged breath. My father seemed to struggle so. The hospice nurse had told us that my father could still hear us and we could talk to him, give him permission to die. My brother and I stood on either side of the bed, unpracticed and awkward with this speech. “You can go now, Dad…” I began. My brother started to cry. I can’t do this,” he told me, fleeing the room.

The last morning I woke early, made a strong cup of coffee, and went out to the porch. I held my father’s hand and told him how lucky I was to be his daughter. How I always felt so secure in his love. Then I told him he could go. I told him I was married to a good man now. I had a secure job. And yes, I had enough money. I promised him I would take care of Mom.

I told him to go. I was forceful, even. I said I wanted him to go. I said things I didn’t even believe. About going toward the tunnel. Following the light. I told him his own mother was waiting for him. I felt myself almost pushing him out of this life. “You can go now, Dad,” I repeated.

At eight o’clock Beverly, the nurse we had hired to help at the end, came. “It’s almost time,” she said. “Wake your mother and brother.”

There were three last breaths, three noisy rattles that I thought were the last. But my father’s final breath was actually a gentle poof—as soft as a baby’s sigh.

Death doesn’t end a relationship. My father is still in my life. His love and humor; his steadfastness and competence and strength. He was a man you could trust. That is the legacy that he has given me.

I had a remarkably happy childhood. A friend of mine says that I grew up in the only really functional family she can think of. I don’t know if this prepared me for the losses and hurts I experienced as an adult. I like to think it did—that as Eskimos are padded with layers of fat to protect them from the cold, I was cushioned in childhood by layers of love to help me through painful times.

My father, a businessman, was very practical. He listened to news rather than music on the radio. Except for The Times and The Wall Street Journal, he was not a reader. I don’t recall that I ever saw him read a single novel. Yet he was very proud of my vocation and had read every word I ever wrote (He was critical only of the occasional sex scene in my books, which he considered “not necessary”).

At the end of his life he gave me Power of Attorney and the key to the vault and told my brother and me where the stocks and bonds were. He told me to put air in the tires of the car. He told us he wanted his body to be cremated. He also asked me, a week before his death, to write something about him. And so I did.

Beautiful, Fern. I'm in tears.

Oh, Fern. Just broke my heart reading this. How fortunate you were/are to have trustworthy, loving men in your life. Your father's practical yet caring spirit shines through these lovely words. Your writing amazes me.